| |

Οι Εμπειρίες τoυ κ. Πουλαράκη |

|

| |

Ioannis Poularakis

The University of Tokyo, Graduate School of Engineering, Department of Architecture, Chiba Lab, Master Course / April 2010 – March 2012

The Monbukagakusho (MEXT) Japanese government program of international scholarships represents an efficacious tool of congenial, proactive diplomacy; it is not only a means to spread scientific knowledge and expand Japan’s cultural influence, but also a potent promoter of international cooperation and peace.

Students and researchers from disparate countries are equally offered the opportunity to live and study together in a safe, hospitable and civilized environment. In such optimal conditions that allow for unrestrained mingling of ideas and genuine cultural exchange, MEXT grantees commonly accomplish to transcend nationalistic, religious, or racial preconceptions and antagonisms, and achieve to develop cordial and long-lasting interpersonal bonds. In some, if not all, cases, these personal relationships may induce a multiplying effect, thus becoming catalysts of international understanding.

For this invaluable contribution to world peace, as citizen of Greece and as a human being, I cannot thank enough the Japanese government, the embassies involved, and, most of all, the Japanese tax-payers who generously sponsor this scholarship, despite the -at times- adverse economic circumstances.

|

“Mata Koko Kara” *

There are certain periods in one’s life in which intense memorable experiences are succeeding one another in a rapid pace, causing time to appear incredibly condensed. This is definitely the case of my two-year studies in Japan. Not only because living in the Land of the Rising Sun comprises -as for most Westerners- of countless noteworthy peculiarities, but also because I was destined to witness one of the most dramatic combinations of catastrophic events in human history: the 9M Tohoku earthquake, the devastating tsunami and the consequent nuclear accident in Fukushima Dai-ichi power plant.

Attempting to comprehensively present the entirety of these experiences, in few lines, would be an insurmountable task; therefore I will only briefly outline my academic experiences, and those of the volunteering reconstruction program in which I participated.

|

|

Studying Architecture at the University of Tokyo has been a lot different than at the Italian and American universities that I had previously attended. According to the Japanese system, every student is assigned to a Professor’s laboratory and, usually, all academic life, design work and classes gravitate around it. Meetings, extra-curriculum projects and competitions, as well as field trips and guided visits are also frequent events of laboratory life.

Visiting, together with Prof. Chiba, some of Japan’s most exciting contemporary architectural projects, and listening to his on-site lectures has been a highlight of my studies; a rare opportunity and a great privilege.

|

There is a vivid and dynamic atmosphere in the School of Architecture, with all the, in-house and visiting, world-famous architects offering classes and lectures of high academic value.

One is free to arrange their course of studies according to their specific interests, and significant freedom is given to individual research topics. Passing exams and obtaining course credits, generally, presents no substantial difficulty. Commitment, attendance, perseverance, and hard work on the other hand, are greatly valued and, needless to say, required from everyone. |

In my opinion, one of the most difficult issues for a Greek student in the Japanese university, and society in general, is to comprehend and assimilate the complicated rules of communication and decision making processes that are strictly connected to hierarchy, manners of politeness and behavioral patterns. Being opinionated, capable of fierce argumentations, and openly expressing disagreement or criticism, may be considered virtues to be encouraged in the Greek society and education; however, they are definitely perceived as inconveniences in the Japanese society, where respecting the rules and following the person in charge, or the superior in hierarchy, are unquestionable requisites. Although there is significantly greater tolerance towards foreign students on this regard, it is advisable to make an effort and conform to the Japanese modus operandi. |

During the course of my studies I have had the opportunity to undertake architectural projects dealing with contemporary matters of the Japanese society. For example, I have worked on a hybrid office typology, incorporating leisure activities for the improvement of office-workers’ well-being, as well as facilities of basic healthcare and sanitation for the support and re-introduction of Tokyo’s homeless to the job market.

Another interesting topic was that of a residential complex for the elderly, with communal kitchen/dining. This proposal tackles the problem of entire areas -especially in the suburbs- being left only with elder residents and vacant houses because of Japan’s aging population. |

|

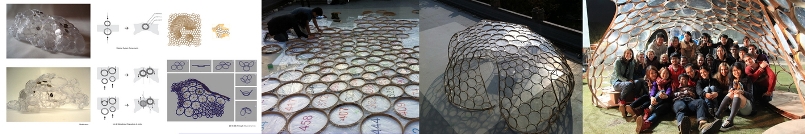

An experimental project, that I am particularly proud of, is that of a circle-packing, tensegrity structure, developed for Digital Matters G30 Studio. The invented material system prototype -consisting of a Concentric Rings rigidifying compression element, that attributes structural capacity to PE sheets- has been further advanced by Professor Obuchi’s G30 laboratory, after my departure. A real scale model has actually been built and exhibited in Tokyo Designers Week 2012.

Among the architectural competitions that I had the chance to participate in, I would like to mention “Vertical Cities Asia” invited competition. Ten of the world’s best schools of architecture competed on the theme of highly dense, vertical cities, with particular attention to their environmental aspects and social sustainability. We presented our proposal in Singapore in front of an international jury of prominent architects, including Pritzker-prize-winner Wang Shu.

This competition led to my final Master thesis, entitled “Housing Density: from Existenz Minimum to Existenz Optimum”, which investigated the architectural parameters that enhance livability in high-density conditions.

|

In spite of these exciting academic experiences, it was the earthquake of March 11th 2011 and the consequent tragic events that had the strongest impact on me.

In the frantic situation of mass panic that followed the disaster, my friends and relatives persistently insisted to withdraw from my studies and leave the country permanently. Despite these calls, and the uncertainty of how severe the radiation risk was, I got deeply moved and inspired by the dignified stoic stance of many Japanese people around me. Hence, I procured a portable Geiger counter, and decided to continue my stay. Moreover, I joined a volunteering university re-construction program in one of the locations that was heavily hit by the tsunami: the small port-village of Shibitachi in Miyagi prefecture, close to the city of Kesennuma.

Fukushima-based architect and journalist Toshihiro Sato, joined forces with Professor Hiroshi Ota of the University of Tokyo, and many other volunteers (architects, professors and students of architecture), in order to bring our technical assistance and architectural expertise to the destructed area.

|

|

My first field trip in Tohoku was in July 2011, after the major emergency operations had been effectuated and the main streets were clear from mud and debris. Nevertheless, the situation that we encountered, in the city of Kesennuma, was still devastating. Heavily damaged buildings and enormous mountains of piled up materials could be seen everywhere. Words and pictures cannot describe the horrible smell around the port area of the city… Smell of rotting fish and excrements mixed together. Ten thousand people were missing, and while walking among the ruins we had no doubt that among those shapeless masses of crashed buildings, cars and boats there were certainly trapped corpses…

Kesennuma appeared as a vast demolition site where cleaning teams had been working for many weeks incessantly. Yet, there were no yelling, no shouting, no unnecessary noises. Except of the sound of the machinery, allover there was a piercing silence. Emergency workers, volunteers, evacuees, kept a respectful stance towards those who had lost their lives.

|

The situation in the village of Shibitachi was not much different: ruins, rubble and vast destruction. Shibitachi is a fishery village renowned for fresh seafood and for the extended aquacultures spread in picturesque bays. Due to the particular geomorphology, Shibitachi was severely hit by the tsunami, since the inundation reached, at certain points, over 10m of height. The lower part of the village was swept away, and the local community mourned 7 losses.

|

|

Our host and guide in the area was Shintaro Suzuki, a noble, gentle man, prominent and respected in the local community. He honorably carried on a long family tradition in Karakuwa Peninsula. His heritage, consisting of an old manor house, several wooden warehouses (kura), a complex of commemorative rocks of his ancestry, and a private temple in the woods, constitutes, literally, a living open-air museum. Luckily, they were all saved from the tsunami. Several structures, however, had suffered significant damage by the seismic force. Our team spent few days performing architectural surveys of the old buildings, and I, personally, had the great opportunity to make detailed measured drawings of part of Suzuki’s house.

Our main duty in Shibitachi though, was to redesign the destructed port area and to propose a security plan for future disasters. To do so, our leaders proposed a bottom up approach, were all brainstorming and decision making were to be made in close collaboration with the locals. This process required several visits in the area, and tiring as it was, produced amazing results: not only we arrived to a reconstruction plan full-heartedly supported by the community, but also strong personal bonds were created with the local residents. We were not seen as some techno-bureaucrats making top-down decisions, from the comfort of their laboratories in Tokyo, but real persons who were visiting once every while voluntarily and cared about their opinion and will.

We conducted topographic surveys, produced physical and digital models and proposed a concise reconstruction plan. This is an ongoing project and I was really saddened that my participation was interrupted by the completion of my studies.

|

|

The collaborative design strategy developed in Shibitachi is probably one of the two most significant lessons of my stay in Japan. The other lesson is the tireless spontaneous commitment that the average Japanese citizen feels towards their homeland and community.

The silent, courageous emergency workers of Kesennuma, and the generous altruistic volunteers that we encountered everywhere, offer a paradigm of perseverance particularly meaningful for Greek society: keep going, never give up, whatever the disaster, however huge the pain! A new bright future will rise from the ashes! Until the next disaster, that will unavoidably come.

|

As a young student in Tohoku wrote: “Mata koko kara”.*

*(Start over) again from here.

←Εμπειρίες Αποφοίτων

|

|

|

|